Today’s practice: Listen carefully to the slightest twinge of discomfort about how you’re interacting online. It’s there to help you learn to follow your own principles online.

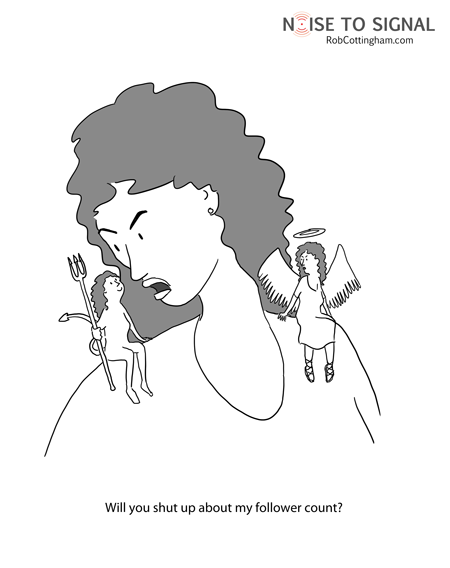

Noise to Signal Cartoon

Whoever said “it’s better to give than to receive” had to be talking about advice. Giving it is fun: it makes you feel wise, generous and smug, all at the same time. Getting it, and especially following it, is a lot harder.

That’s what struck me as I struggled yesterday to adhere to the very principles I laid out in the Social Sanity Manifesto for HBR. Here’s the one I found toughest yesterday:

I will not judge others based on their online metrics. I’ll reply to emails and mentions based on my interest and availability, not the Klout score or follower count of the person who is writing to me.

True confession time: engaging with HBR readers is probably the number one contributor to metrics abuse in my own online life. My HBR posts are typically retweeted a few hundred times, sometimes into the thousands. That’s more than I can reply to, so I have to choose which tweets or comments will get a reply.

One of the factors that’s guided my replies is the desire to help people connect my posts to my username. The vast majority of tweets about my HBR post link to HBR, or mention @harvardbiz, without mentioning me as @awsamuel. I always hope that more people will connect the dots, and start following me back. That leaves me skating awfully close to point 3, “I will not game online metrics”.

Up until yesterday, I relied on various sketchy measures of influence in order to focus my attention and replies. I usually set up a HootSuite column searching on keywords I imagine will be tweeted in links to my HBR post, and though it pains me to admit this, I’ve often filtered that column by Klout so that I see just the Klout-ing-est tweets and reply to those. And I also use Topsy.com to see everyone who is tweeting a link to my latest HBR post, but check the “show influential only” box so that I can just focus on replying to people who are Very Important Social Media Users.

Yesterday, I foreswore these practices. It was a bit anxiety-producing, because these tactics have helped me ensure I thank people who have lots of followers. If I don’t thank them, then how will they know to follow me, tweet my every word, and add their millions of followers to my own?

Here’s the other truth. As you may have noticed, I don’t actually have millions of followers. All this busy influence-filtering has perhaps had some impact over the past couple of years, but it hasn’t been earth-shattering.

But it has been soul-shattering. Every time I’ve used these influence-filtering techniques, I’ve felt a bit icky. Every time I’ve demonstrated these influence-filtering techniques, I’ve felt ickier. And when I recently taught these techniques to a roomful of students, I felt downright corrupt. Was this really how I wanted to teach people to use the Internet?

No, it’s not. And if it’s not good enough to teach, it’s not good enough to do.

So here I am, trying something different. I’m still thanking people who tweeted my post, but I’m thanking the people who did mention me, rather than focusing on those who didn’t. I’m thanking some of the latter, too, but I’m picking out the most interesting or thoughtful tweets rather than allocating my attention based on the metrics-based “value” of the tweeter.

As a result, I had an energizing day of conversation. I got to think about what people were saying, instead of focusing on the numbers. I had a few actual back-and-forth exchanges with people, and I started following a few new people myself. I started a new list of people who were interested in this post, and who I hope will a source of further conversations ahead.

The lesson, in all this, is about more than judging people by the content of the tweets rather than the number of their Klout. It’s about listening to that inner ick, whenever it appears; about paying attention to the inner voice that tells us we’re transgressing some fundamental human principle in our interactions online.

We’re all babies, here, learning how to live online. Our digital moral compass is still calibrating, and the inner voice of conscience often whispers when we need it to shout. So get really, really quiet and listen, because it may be telling you something very important about who to spend time with online, and how to treat them.

Recent Comments