Those of us who enjoy the professional and personal benefits of remote work are a large and lucky minority—but yes, a minority. Most estimates show that about 60% of North American jobs just have to be done in person.

Not incidentally, these are jobs that are more likely to be done by people of color, by less educated workers, by younger workers, and in many countries, by women. One of the major reasons that Covid disproportionately affected communities of color is because people of color had less opportunity to work from the safe isolation of their own homes.

Reckoning with this divide—the gap in experience and opportunity between those of us who can work remotely, at least part of the time, and those who must do all of their work in an actual physical workplace—is the next big challenge for organizations and for society as a whole. That’s why I highlighted the issue of hybrid equity in my forecast for Microsoft’s Future of Work report, published today.

While many organizations are giving a lot of thought to their hybrid transition, most of the attention is on the employees who’ve been remote throughout the pandemic: How do we get them back to the office? How much of the time will they spend on site? How much control will they have over their specific schedules?

These are crucial questions, but they obscure other foundational problems: How can we build a sense of common culture and mission if our organization is split between on-site and hybrid employees? How can we ensure pathways to mentorship and advancement if junior, on-site workers barely interact with mid-level hybrid employees, or have only limited opportunities to learn the online collaboration skills that are increasingly essential to hybrid work? How can we develop a model of work-life balance and personal wellbeing that is available to on-site employees, as well as those with the flexibility to work remotely?

Creating a hybrid equity strategy

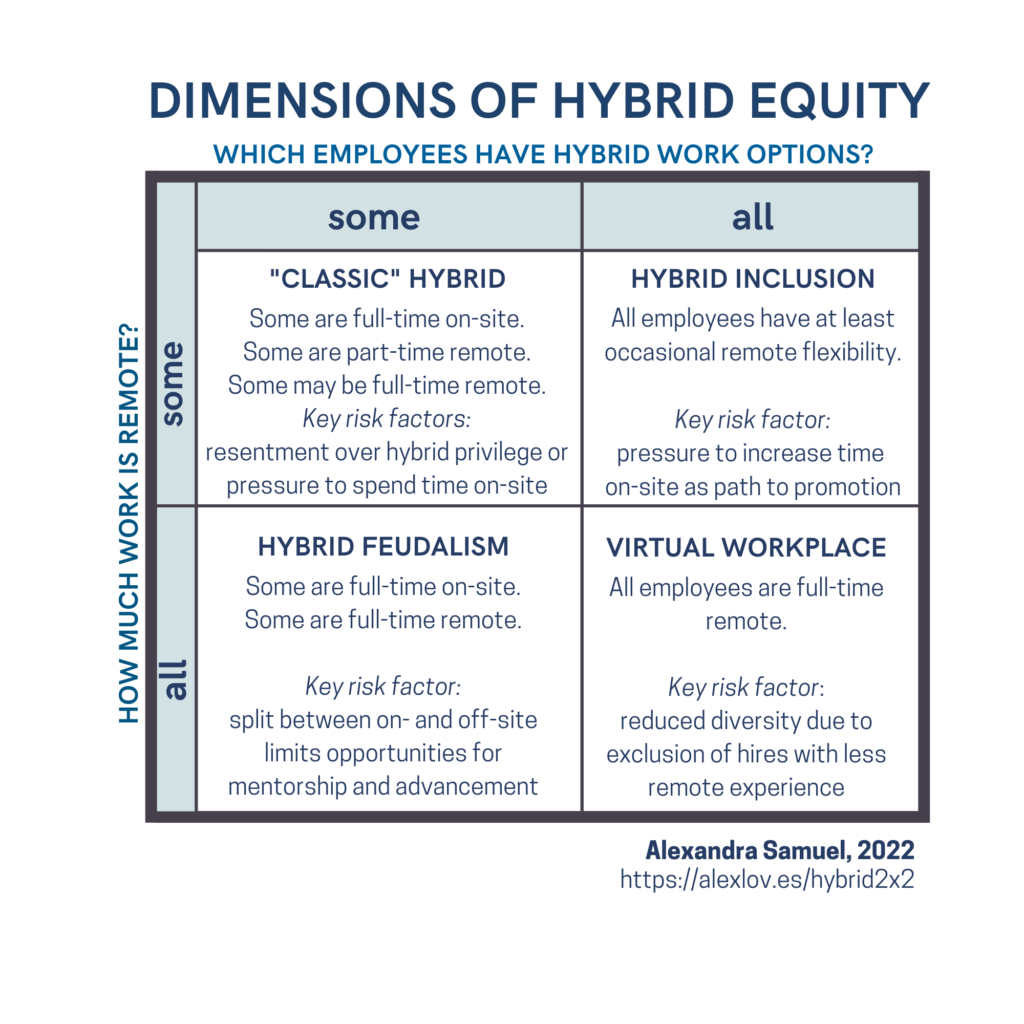

The way organizations address these questions—or fail to address them—will determine the shape of organizational culture and organizational success for years to come. I’ve mapped the key dimensions of this choice: It comes down to whether some or all of your employees have access to remote-work flexibility, and whether they work remotely some or all of the time.

In the best-case scenario, organizations will opt for hybrid inclusion, finding ways to offer at least some measure of flexibility to literally every employee in the organization. That may sound like a radical idea, but even a half-day each month of “flex time” helps accommodate medical appointments, kid emergencies or just a little bit of peace and quiet while you take care of remote-feasible work like filling in timesheets. While the cost of that flex time could be substantial, in many organizations it will still be significantly less than the cost of motivating or replacing on-site employees who accumulate resentment towards hybrid colleagues.

What matters most, at this moment, is to put the issue of hybrid equity on the C-suite’s agenda. It’s time to pay attention to who has access to remote-work flexibility, how that flexibility affects advancement opportunities, and how we are building relationships between on-site and hybrid teams. The most successful organizations—the ones that will deliver great customer experiences, and attract and retain great talent—will be those that develop strategies, tools and rituals that connect on-site and hybrid employees, and build a common experience of hybrid inclusion.

Because bringing people back to the workplace can only go so far if we fail to think about those who have been there all along.

Recent Comments